Designing Chicago’s Streets of the Future

Introduction

We are entering a new era of mobility – and our streets will need to adapt to future changes. There are shifting patterns in where and when we travel, whether for work, school, services or entertainment. We are embracing hand-held technologies giving us real-time information on transit service, on-demand cars and optimal route selection. We are installing telecommunications infrastructure for faster connections to emerging technologies. Our hardware is changing too, from scooters to early semi-autonomous vehicles and new types of buses. We are demanding more out of our streets every day – from ride-share to next-hour delivery.

Dynamic change has led to some dynamic debate about the type of streets cities need, and want, in the future. There have been long-view urban design speculations, promotional concepts by technology developers, plans for entirely new cities and districts, and guidance from transportation-sector organizations.

For new cities and urban districts, a blank canvas approach can be taken to designing new streets. Cities such as Chicago, on the other hand, are mature cities with an established structure and fabric.

The next generation of streets will not look like a futuristic sci-fi film. Scrapping entire road systems is not feasible, so we must take the approach of understanding the assets that we currently have and can maximize. At the same time, we have certain expectations of what our streets should look like and how they should perform – ranging from safety to economic development and transportation network connectivity goals. From Chicago’s historic commitment to maintaining parks, boulevards and streetscaping, this ‘Urbs in Horto’ – ‘City in a Garden’ – cannot neglect landscaping and trees. Those same beautification efforts play an essential role in reducing heat island effects and creating and maintaining habitat for birds and insects (and squirrels).

In this age of concern about climate change, we should also expect that infrastructure enhance sustainability. Spaces that encourage people to walk, bike and use transit will reduce carbon footprint. Solar power should also be incorporated into our infrastructure, and new transit shelters, lights and communication equipment can allow for that.

Chicago’s streets of the future can also focus on improved efficiency, and seamless transportation between modes, with a keen eye for filling gaps in equity and inclusion efforts. Technology should not be implemented without exploring how it will benefit all residents.

So, what should Chicago’s streets look like in the future? Skidmore, Owings and Merrill LLP (SOM) teamed up with City Tech to address these questions and see what the implications of these disruptions could be for Chicago’s streets. Along with inputs from mobility companies, technology specialists, advocates for micro-mobility and autonomous vehicles, and planning and transportation agencies, we have carried out an investigation of “ Chicago’s Streets of the Future

,” a thought piece and open investigation which we believe has brought a number of conversations into the same space.

Process Approach

We invited subject-matter experts to attend two design sessions in 2019 to provide input on current demands in transportation, emerging trends, and how those elements might factor into future design and operations. Through this process, we developed a set of ideas about how our streets could evolve over the next 10 to 30 years, then modeled design concepts on some typical Chicago streets. These prototypical designs illustrate strategies that could be deployed throughout the city in similar environments. This exercise was designed before the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, but we believe the technology-enabled flexibility and long-view of mobility trends still hold and provide a starting point to incorporate new priorities.

For this effort, it was important to engage cross-sector stakeholders to gather multiple perspectives and priorities in terms of emerging technology trends and behaviors. Creating an industry-level vision required input on what technology is available, the nature of its adoption, what technology is emerging, and its highest and best uses for residents and service providers. Participants brought expertise in mobility, technology, urban planning, engineering, policy, and research and represented the public, private, non-profit, start-up, and academic sectors. We hope this collaborative process has led to a more informed, aspirational and practical outcome.

Street Requirements & Components

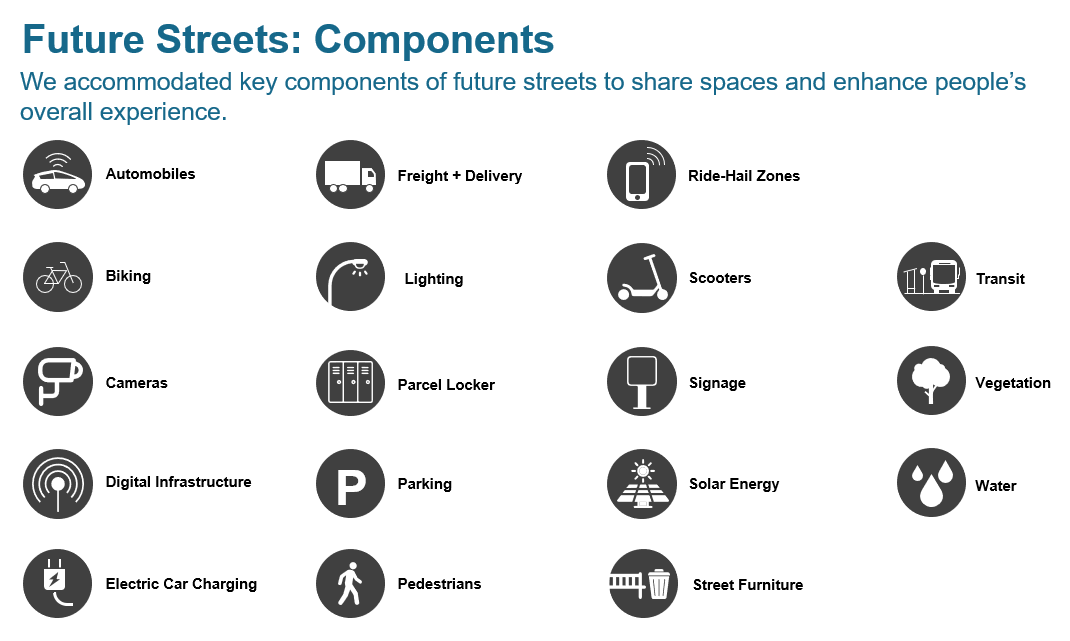

This investigation has looked at a range of new performance and physical requirements that Chicago’s streets will need to meet to accommodate new technologies, equipment and mobility behaviors. In addition to new digital infrastructure, we wanted to consider the freight and logistics, public transit, personal vehicle, biking and walking roles of streets.

Our approach emphasized technology-supported flexibility above all. Technology led some design decisions, while others were influenced by the rapidly evolving personal choices of cities’ residents and workers. These include maximum mode flexibility and interchange, walking, biking in the public domain and an increase in deliveries to homes.

We wanted to see how these trends could translate to design directions and physical solutions on the ground using real-world examples. As we explored these future-street concepts, it was important to remember the various conditions across the city, such as:

- Street types : major cross-town routes, neighborhood commercial corridors, residential blocks

- Street classification s: arterials, collectors and local

- Locations: North Side, West Side, South Side and Central City

- Public transit functions : bus and no current bus service

- Dimensions and lane configurations : various rights of way and roles of turn-lanes

- Landscape character : medians and parkways

Rapidly changing technology drives an increasing

demand for urban sensor networks to monitor and manage environmental and

security conditions as well as new communications to enhance transport

efficiency and guide and operate new technology. Both create demand for new

infrastructure.

Not all streets will have all components, but

there are some essentials which will be everywhere.

Mobility Behavior Trends

Exploring the future of our streets also meant acknowledging trends in urban life. The investigation focused trends such as:

- Technology-Enabled Journeys: For many, a typical day includes walking to a bike dock, cycling to another dock, and hopping on a bus to go to work. A similar evening or weekend trip might entail using a ride-share service vehicle. The efficiency of these modes is enabled by access to real time information on routes, common payment, connections and mode swaps. This typical technology-enabled journey is less than a decade old.

- Changing Work Hours and Work Locations: Changes in work mean a focused 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. downtown and fixed shifts in large manufacturing plants elsewhere have been replaced by a more expansive Central City, working at home and while on the move, less dense employment in local industrial corridors, new shift timings and the gig-economy.

- Consumer Habits: New consumer habits are trending to more home deliveries and more frequent trips to grocery and convenience stores. The role of our streets is also changing, with evolving trends in street retail and sidewalks seen as spaces for public activity, gathering, socializing and dining.

All this means rush hours are morphing, and movement in cities such as Chicago is becoming more complex.

Macro Assumptions

Urban mobility is a rapidly evolving field. The

conversation about the future is happening within multiple domains: vehicle

technology, public policy, revenue raising, traffic modelling, user experience,

spatial form and the future economy.

Before considering design solutions, we observed

current trends to anchor the following assumptions such as:

- Individual car ownership will decline. This will be a result of many factors: lower use in coming generations, the increased efficiency and appeal of transit, the use of bikes and walking, the role of micro-mobility, sharing of vehicles within trips and among different users, increases in home delivery and denser urban development where homes and jobs will be closer together.

- There will continue to be a street hierarchy – with higher volumes and higher speeds directed to interstates and arterials with fewer intersections. Not all vehicle types will go everywhere. Local and residential streets are often more attractive, safer and quicker for cyclists. Cycling will grow, but not every street will have a bike lane.

- Pedestrians should be supported everywhere . Walking connects us between modes, and those transfers should be as seamless as possible.

- Vehicle queueing and the time required to allow people to enter and leave vehicles at curbside means higher density districts will be best served by transit, bikes, micro-mobility and walking rather than cars, even those that may be autonomous or shared.

- Street parking can be reduced but will not disappear completely. Traditional long-term parking for local residents may be reduced the most. Residential streets may see the greatest decline, in line with reduced individual car ownership. Visitors and service providers will still need in and out space.

- Ride hail and rideshare services will continue to grow, exploring integration with autonomous technologies and public-private operations. Cities will continue to develop policies to control the impact of these evolving modes, and guide pick-up/drop-off operations within their boundaries.

- A new generation of vehicles will emerge , with capacity for 8-20 people, whether through ride-share services or future transit providers. These will have more-nimble, on-demand routing, can serve lower-population-density areas and will connect to, or supplement, higher capacity fixed transit routes.

- Autonomous vehicles will have a role , but we may be in a hybrid system for some time as technologies are perfected and the cost and construction impacts on public infrastructure are absorbed.

- More immediate consideration should be given to the rise in electrification and demand to power both private and shared vehicles.

- The recent increase in total vehicle miles travelled , often ascribed to new rideshare services, will be mitigated by nudge economics and taxation to reflect the increased pressure on, and use of, infrastructure.

- On-site vehicle storage will continue . Outside of peak times, some cars will need to stop remaining relatively close to their users or market. Constant motion on streets or deployment to remote lots will add to the total vehicle miles travelled, add maintenance costs and reduce the lifespan of infrastructure and vehicles alike, while reducing energy efficiency and sustainability gains.

- Services should be provided equitably across the city.

Some of these assumptions could be challenged over time, but we see most of them holding for the next 10, 20, and 30 years.

Key Strategies

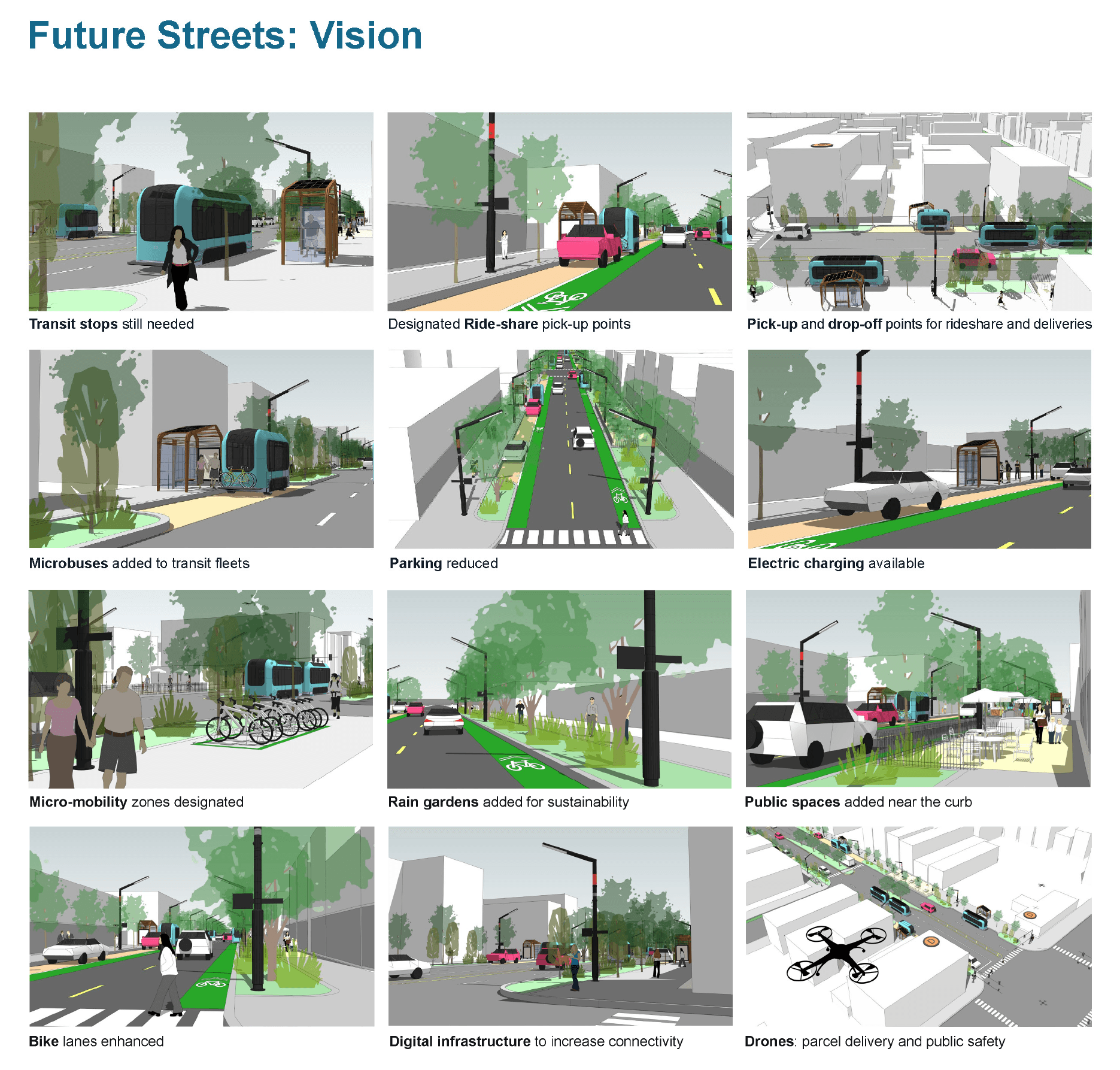

During this exercise, several strategies emerged to inform our visions of future Chicago streets. These may be deployed to various degrees across street types and are adaptable to the unique conditions of our neighborhoods.

- Rethinking the curbside zone. Most of Chicago’s streets currently use the curbside zone for street parking and bus stops. As demand for parking decreases, we can imagine a mix of systems staking claim to this space, optimized for particular block conditions or times of day.

- Flexible, shared drop-off/pick-up areas. The reimagined curbside space can adapt to emerging modes of transit and delivery, allowing for conventional buses and trucks as well as rapidly evolving autonomous shuttles and rideshare. Street parking can phase out in accordance with demand areas.

- Flexible, shared streets. In low-traffic communities, streets can be designed to mix pedestrians and low-speed, responsive autonomous vehicles. Or, depending on time of day, streets may adapt from vehicular accessible to pedestrian-only.

- Expanded natural landscape and stormwater management. Space gained along the curb can be utilized for rain gardens that naturally convey and cleanse stormwater or additional trees that shade our streets and sidewalks, increasing bio-habitat and reducing urban heat island effect.

- Smart infrastructure. A new generation of technology will be required within our public rights-of-way. We envision flexible, modular poles that accommodate lighting, sensors, traffic signals, security systems, and power generation where possible. Poles can adapt to street-specific demands and upgrade to newer technologies as they evolve.

- Increased space for people. In some communities, demand may be greater for additional space for pedestrians, sidewalk dining, play areas or dog walks. We can convert former parking lanes to potentially double the amount of public open space that exists along most streets today.

- Flexible delivery options. Whether through flexible curbside space for freight parking or drone landing zones on flat roofs, the rise of e-commerce was a key component of how our streets will be shaped.

Sharing the Vision

With these urban trends, assumptions and design

strategies in mind, we have crafted a visualization of Chicago’s future

streets. Our design exercise does not simply end with the attached

presentation.

As noted previously, future streets likely will

not mirror sci-fi films, however, they will be highly capable transit networks

that are multi-modal, digitally connected, and more socially and

environmentally equitable. This investigation revealed that vision necessitates

strategic design that balances the form and function of technology with changing

demands created by evolving behaviors.

Cross-sector expertise informed this vision . Successfully

implementing elements of this vision calls for continued collaboration among

the private, public, and non-profit sector as well as residents to ensure all

the pieces fit together and deliver pragmatic outcomes that represent widely shared

priorities.

Through the

Advanced Mobility Initiative

, City

Tech and SOM are actively engaged in developing solutions to urban mobility

challenges. This vision and the input from the participants who helped create

it will help guide decisions that shape future streets in Chicago and offer a

more seamless, productive transportation system.

We hope sharing this vision serves as an opportunity

for you to explore your thoughts on streets of the future, whether in Chicago

or your city or community.

As you review the work, we encourage the

following considerations:

- What are the most prevalent challenges you face (i.e. first-last-mile connectivity, curb congestion, safety, etc.)? Does this vision support viable solutions?

- What role would you play in cross-sector collaboration? What support would you seek in cross-sector collaboration? And, what tends to be the barrier to successful, strategic partnerships?

- As transportation modes evolve, should future streets designate specific uses such as bus-only, bike-only, or car-only? Or should infrastructure be flexible allowing organic, coexistence of uses?

- What type of financing models could support large-scale infrastructure developments and maintenance? What are other requirements for implementation?

Click here to view the results of our design exercise “Chicago’s Streets of the Future” at City Tech’s website , or d ownload the full exploration.

About the Authors:

Chris

Hall

is an

urban planner and Urban Strategy Leader in the Chicago office of Skidmore,

Owings and Merrill. Thomas Hussey

is an urban designer and architect and

Director in the City Design Practice in the same office. Both are long-term

Chicagoans with portfolios that encompass major local, national and

international projects. Jody Zimmer served as urban designer for this process.

Kate

Calabra

is the Partnership

Development Manager at City Tech where she works to facilitate strategic

partnerships and collaboration to build solutions for critical city challenges.

Prior to joining City Tech, Kate was a Senior Associate at the American

Planning Association and Fellow at the Metropolitan Planning Council.

About City Tech’s Advanced Mobility Initiative

This exercise

was one of many projects of City Tech’s Advanced Mobility Initiative, an effort

involving 25+ industry partners to create a more seamless and frictionless

transportation system with increased accessibility and reach for urban

residents. The Initiative includes six impact areas that City Tech will address

through thought leadership, resident engagement, and solution development.