The Robots Are Coming, but This Time Really Can Be Different.

Preparing Our Workforce for the Next Technological Disruption

City Tech accelerates technology-enabled solutions that address society’s

most challenging urban problems, and in doing so, makes our lives happier,

healthier, and more productive. We are successful when we help our partners use

new and emerging technologies to disrupt

our environment. These

disruptions unlock capabilities that enhance our infrastructure, make our

services more efficient, and reduce costs, all with the ultimate goal of

improving our well-being. However, history has shown that widescale adoption

of new technological solutions will displace workers whose occupations are

dependent on the old conditions, resulting in unintended economic, health, and

social consequences

( 1).

The automobile, telephone, and computer are popular examples of

inventions that ushered in societal-level creative destruction by replacing

horse carriages, telegraphs, and typewriters. These technologies created rewarding

opportunities for future mechanics, technicians, and engineers, but they provided

little comfort to the blacksmiths, telegraph operators, and clerks who lost

their livelihoods ( 2).

The effects of technology-driven displacement create economic

“winners” and “losers” throughout society and exacerbate wealth and social

inequalities.

Those with high levels of education, in-demand technical skills,

and resources to withstand a temporary income loss are well-positioned to take

advantage of emerging employment opportunities. The negative effects are more

concentrated in certain segments of our population, and the short-term options

available to replace the lost jobs (such as work in agriculture, retail,

services, and entertainment filled with routine tasks) are often low-paid and

without substantial opportunities for career advancement. Black, Indigenous,

and people of color, as well as women, foreign-born workers and individuals

with low levels of education are the most vulnerable of getting trapped in

low-wage jobs with little prospects of economic mobility ( 3, 4).

More recent examples of technology-driven displacement include the

closure of a large number of brick-and-mortar retailers due to the rise in

e-commerce ( 5, 6, 7, 8, 9),

rideshare platforms devastating the taxi industry ( 10, 11, 12), and automation’s

contribution to the demise of low and middle-skilled manufacturing jobs ( 13, 14). The

most recent period of disruption has been especially painful for low-skilled

blue-collar workers who are most likely to be diverted into the growing number

of low-income service jobs. Since 2000, the high-paying manufacturing sector, which

traditionally has provided many families with stable middle-class incomes, went

from the largest employer nationally of lower-skilled workers to one of the

smallest ( 15, 16). A 2019

Brookings analysis estimates more than 53 million people can now be defined as

“low-wage workers,” or 44% of all workers ages 18-64 in the United States ( 17, 18).

Next, the Robots Come For You

The next wave of technological disruptions in fields such as

robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), telecommunications, autonomous

vehicles, and battery storage are still in their early stages. They have yet to

revolutionize entire industries, but if their advancements thus far are any

indication, high-paying and high-skilled white-collar jobs will not be

spared in the next round of displacement.

AI-enabled

software is not only replacing sales and customer support agents with chatbots

and self-checkout kiosks. It is also automating routine tasks in accounting,

law, financial services and even the detection of diseases in radiology ( 19

, 20

, 21

, 22

, 23

). Improvements

in telecommunications are providing more opportunities for the broad adoption

of online education and telemedicine, threatening displacement among teachers,

professors, and medical and health insurance professionals. Companies such as

TuSimple, Aurora, Daimler, Embark Trucks, HERE Technologies ( 24),

and Alphabet-owned Waymo are all working to fully automate shipping by building

self-driving freight trucks and navigation systems ( 25). Walmart

recently stated that they will start a pilot project to deliver grocery and

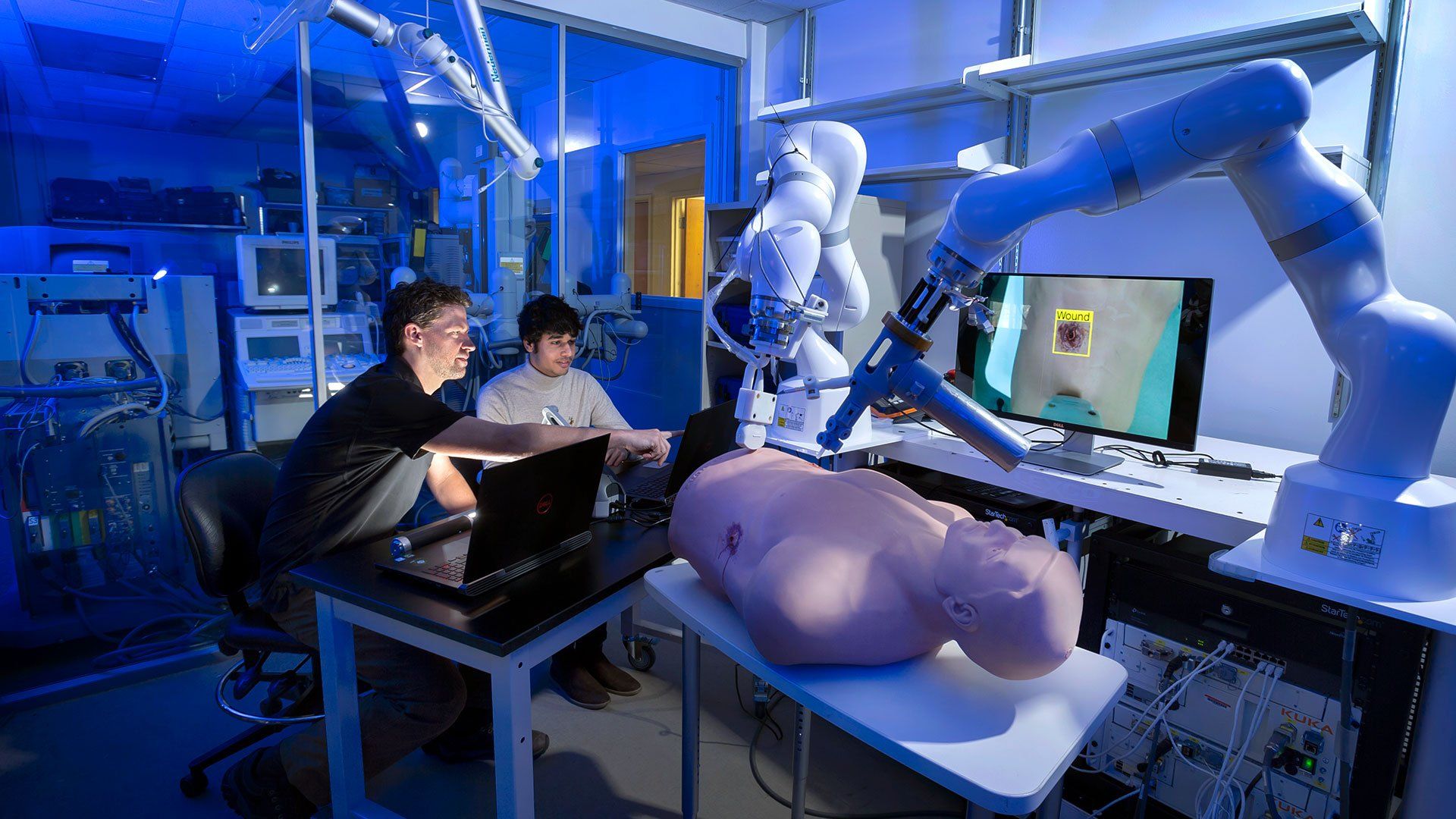

household products through automated drones ( 26). Robots

are cleaning our airports ( 27),

patrolling our buildings ( 28), and

performing more intricate tasks in slaughterhouses ( 29) and

surgical departments ( 30).

Given the prevalence of new technologies throughout the workforce,

dire predictions among experts

( 31), and poor

record of turbulent transitions in prior disruptive phases, it is no surprise

that there is widespread fear across

industries about jobs being eliminated as a result of a new technology ( 32, 33, 34).

We have

formidable challenges ahead of us that must be confronted with decisive,

robust, and collective action, but we are by no means destined to live at the

mercy of robot overlords in a future hunger- and poverty-stricken dystopia. The

challenges we face are also ripe with opportunities.

Telework will destroy some labor-intensive jobs in the education

and health care sectors ( 35), but the

proliferation of platforms such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams, and Cisco’s Webex are

also creating opportunities for individuals to take jobs across the country

that do not require them to work in-person. Medical advancements in robotics,

AI, 3D printing, diagnostic tests, and prosthetics will prolong lives and

create new jobs for specialists, physical therapists, occupational therapy

assistants, nurses, and health and personal aides ( 35). The

widescale application of artificial intelligence, autonomous vehicles, Internet-of-things

(IoT) devices, and robotics will increase demand for a host of occupations such

as data scientists, researchers, coders, software designers, computer

engineers, statisticians, mathematicians, technicians, information technology

specialists, cybersecurity experts, and new professions that are not yet known.

Improvements in battery storage will not only create new jobs in the automotive

industry and its supply chain but will also help accelerate renewable energies

such as solar and wind power, and with them, opportunities for solar

photovoltaic installers and wind turbine service technicians ( 36, 37, 38).

The movement toward more automation will displace many jobs, but

it could also increase productivity without causing high levels of long-term

unemployment if managed properly. A 2018 World Economic Forum report estimated

that by 2025 machines would perform half of all labor hours ( 39).

Machines will increasingly take over the routine white- and blue-collar tasks

that are mundane and susceptible to human error while allowing humans to focus

on the high-value tasks that require flexibility, context, problem-solving, creativity,

adaptability, interpersonal skills, and empathy ( 40, 41, 42).

Machine-automated tasks will replace many occupations of our aging population; despite

a declining workforce, increased machine-automated tasks may actually allow

developed countries to maintain or increase productivity levels ( 43).

Our responsibility is to acknowledge that without action to adequately manage a peaceful transition period, the next wave of disruption and displacement will cause significant and persistent unemployment and economic hardship. Minimally, a temporary increase in job turnover and partial unemployment is likely inevitable. Technology will upend millions of lives, including a higher percentage of previously safe higher-skill and high-paying white-collar jobs. Those who have already bore the brunt of previous disruptive periods – Black, Indigenous, people of color; women; and those with low levels of education – will remain the most vulnerable. However, we can take the necessary actions to prepare our workforce for the new opportunities that will arise and increase the resiliency of our social support systems to provide an orderly progression.

Preparing for the Future

An effective set of policies and programs can reduce anxiety,

uncertainty, and fear of the unknown as well as avoid the most tumultuous

economic, health, and social unrest scenarios.

Successful

elements of extensive workforce, education, and social support structures

already exist and are well documented by policy professionals and academic

researchers, but governments, employers, non-profit organizations, and

individuals all need to take responsibility for the changing environment to ensure

the integral components have sufficient resources and mechanisms in place to replicate,

coordinate, and scale into an effective national system.

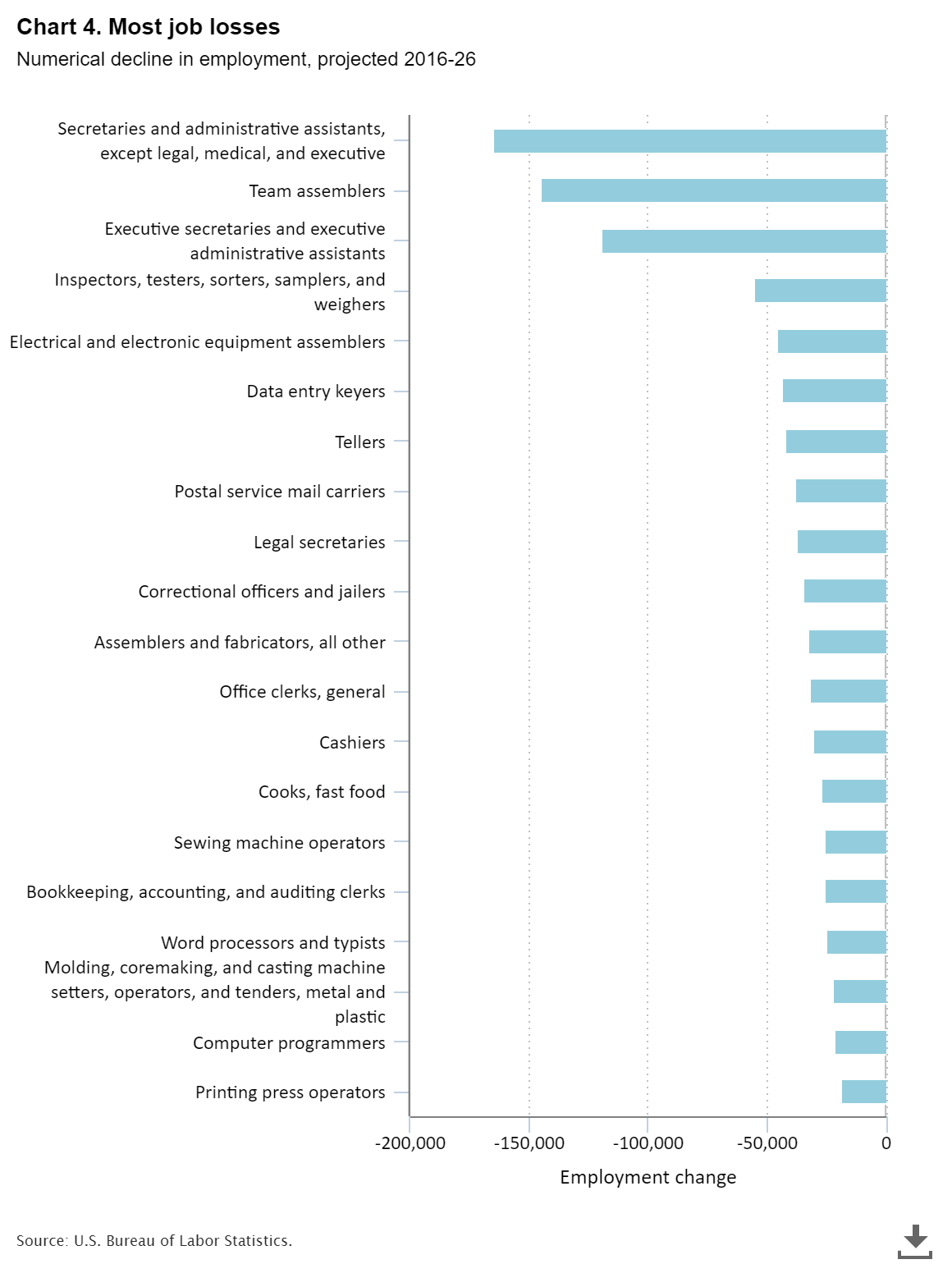

DATA-DRIVEN DECISION-MAKING

First, we need to understand how the landscape is changing the

future job market and communicate this information to public leaders, educations,

employers, and job seekers. What jobs are most in decline and at-risk of being

replaced? What are the fastest growing jobs as well as those most likely to be

created? What are the skills associated with the jobs of the future, and which

skills are most transferrable across in-demand occupations?

Fortunately, it has never been easier to answer these critical

questions and provide stakeholders with accurate demand information and

labor-market insights.

Reports from institutions including the Bureau of

Labor Statistics, Deloitte ( 44

),

McKinsey ( 45

), and Georgetown’s

Center on Education and the Workforce ( 46

) consistently provide in-depth analysis

on these topics. Companies such as LinkedIn, GlassDoor, PayScale, and Burning

Glass also offer real-time labor-market data and analytics on occupations,

companies, skills, competencies, and salaries.

EDUCATION & WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMMING

Next, we must take a comprehensive approach to prepare our

workforce to thrive in the future job market. Our secondary and

post-secondary institutions need to have the right curricula, support systems,

and employer partnerships to ensure our children and young adults can

seamlessly enter the workforce with the right skills to advance in their

careers

( 47

, 48

). There

is a substantial wage premium in the labor market for higher education ( 49

, 50

), but the

continuing decline in college enrollment represents a worrisome trend ( 51

).

A considerable barrier is the increasingly prohibitive cost of higher

education ( 52

, 53

), which

leaves many students entering an uncertain labor market with a crushing debt

burden ( 54

). As

technological shifts will call for jobs that machines cannot perform – those

that require flexibility, context, problem-solving, creativity, adaptability,

interpersonal skills, and empathy – we must make higher education more

accessible to ensure our future workforce is prepared. One potential solution

may be a shift to income sharing agreements (ISA), where the percentage a

graduate pays over a set number of years depends on factors such as their

major, the amount of funding they receive, and their future salary. For

example, Purdue University started offering a promising ISA known as the Back a

Boiler Program ( 55

), where graduates

make payments for about 10 years after graduation. The program was launched in

the 2016-17 academic year, and the fund has invested $13.8 million in Purdue

students from more than 150 undergraduate majors ( 56

).

We must also provide a different set of structures and programs for

existing workers, especially those most at-risk of displacement, with ample

resources and options for up-skilling and re-skilling into jobs with

higher-wages, greater financial stability, and opportunities for career

advancement.

A November 2019 report by Brookings ( 57

)

highlights examples of strategies and evidence-based programs that support

these objectives; for example, Project Quest in San Antonio provides financial

assistance, instruction, and counseling to assist individuals with occupational

training programs at local community colleges ( 58

), and the

state of Washington’s Integrated Basic Education and Skills Training (I-BEST)

is an integrated instruction model combining professional/technical content

with fundamental skills ( 59

, 60

, 61

).

ECONOMIC & SOCIAL POLICIES

Third, we need to be cognizant of the

barriers

that may prevent

individuals from taking advantage of new opportunities, especially the

challenges facing our most vulnerable workers who have been left behind in

previous waves of displacement and paid the greatest economic toll.

We can

implement economic development and social policies that will complement successful

education and workforce strategies, promote the growth of more high-paying

jobs, reduce catastrophic economic and public health shocks, and maximize the

full potential of our workforce.

We have finite resources to invest in our future, and the choices

we make have consequences. For example, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 was

meant to bolster economic growth by reducing taxes on households and companies,

thereby injecting money into the economy and spurring more capital investment

that would generate sustainable growth. After only a slight temporary bounce, the

most lasting effect has been a structural increase in the federal deficit ( 62

, 63

). Worse, the

majority of benefits that accrued went largely to the wealthiest households and

companies in an era with inequality levels last seen in the Gilded Age ( 64

, 65

, 66

). Rather

than boost wages or make transformative investments in human capital, a sizeable

amount of the corporate windfall went to stock buybacks, where companies reward

shareholders by repurchasing their own shares, thereby giving existing

shareholders a larger portion of the company and its earnings ( 67

, 68

, 69

, 70

, 71

, 72

, 73

, 74

, 75

, 76

). And

note: the top one

percentile

of households own half

of all

stocks.

An alternative approach could have used a fraction of the $1.5

trillion price tag – which was mostly financed by debt – to make investments in

community college programs that tailor job training to local employers,

manufacturing extension partnerships, improvements in infrastructure that lower

business costs, enhancing access to credit for economically disadvantaged

groups to start and grow businesses, and scaling best practices with high

returns on investment; such programs include the Accelerated Study

in Associate Program (ASAP) of the City University of New York (CUNY), which

helps students stay on track and graduate by providing comprehensive

wrap-around financial, academic, and personal supports ( 77

, 78

, 79

, 80

).

The American safety net and workplace regulations lag advanced

economies

in workforce protections, employee bargaining power, access to

affordable health insurance and care, unemployment insurance, and work-family

policies such as guaranteed paid sick leave, family leave, and maternity and

paternity leave for all workers ( 81

). As a

result, we lack adequate buffers to stabilize the financial and medical health

of families during bouts of economic insecurity, job loss, and displacement.

COVID-19-related layoffs exacerbated holes in the unemployment

system during the spring and summer of 2020 and overwhelmed antiquated state

unemployment insurance systems ( 82

, 83

), and an

increasing number of job losses appear to be permanent ( 84

, 85

).

However, we can learn from models such as Germany’s “Kurzarbeit” (which

translates to “short-time work”), a work-sharing program that has been credited

with preventing massive unemployment ( 86

). In

addition, we could expand utilization of short-time compensation plans that

already exist in 26 U.S. states and allow companies to avoid layoffs by

reducing hours for employees and then receiving pro-rated unemployment

insurance ( 87

).

RACIAL EQUITY & INCLUSION

Finally, the United States has experienced massive social turmoil and

large-scale demonstrations since George Floyd was killed in the custody of Minneapolis

police in late May 2020 ( 88

). Peaceful

protests, and in some instances rioting and looting, have continued as

additional deaths of Black Americans in police custody have highlighted

persistent discriminatory practices throughout law enforcement ( 89

, 90

, 91

, 92

). The

Black Lives Matter movement has also put a spotlight on racial inequality, a

lack of diversity, and discriminatory policies affecting Black Americans, as

well as Indigenous Americans and people of color, that are pervasive throughout

our workforce ( 93

, 94

, 95

, 96

). Of

America’s top 500 companies, only 1% - four to be exact – are run by Black

chief executives ( 97

).

Still, women,

Latino, and Black workers are all overrepresented among low-wage workers, and

there is sufficient evidence to suggest that their disproportionate share is

due to labor market discrimination ( 98

, 99

, 100

, 101

).

Simple policies can help increase the diversity of our workforce.

A “soft”

affirmative action policy that is easy to implement and could serve as a model

to increase the diversity of hires is the NFL’s “Rooney Rule,” which requires

an NFL team to interview at least one minority candidate for a vacant

head-coaching job, general manager position, or other front-office position.

One study found that during the Rooney era (established in 2003) a non-white

candidate is about 20 percent more likely to fill an NFL head coaching vacancy

than before it took effect ( 102

). A

similar study showed that hiring policies requiring the interviewing of

qualified Black candidates to reach a specific Black-to-white ratio for all

teachers in a Louisiana school district significantly increased the share of Black

teachers without any negative impacts on student achievement ( 103

).

We can do everything right to help our most vulnerable populations

for the next technological disruption

– use data to inform our decisions, educate

and train our workforce on the necessary skills, and implement economic

policies and social safety nets – but nothing will change if discrimination

continues to impede hiring decisions.

Structures and affirmative action requirements

can help facilitate upward mobility in our workforce, but ultimately, we must

dismantle the racism and systematic disparities that plague our businesses and

all aspects of life.

COLLABORATIVE EFFORT

As an urban solutions accelerator, City Tech works with our

partners to use new and emerging technology to disrupt the status quo for good.

Technology has the potential to solve complex problems, but new technology,

capabilities, and business models can have ripple affect across industries.

Working collaboratively across sectors and directly engaging residents

ensure

that we have a broad and deep understanding of the impact of these new

solutions, as well as provides the opportunity to address potential issues and

barriers at the forefront.

For example, the Chicago Health Atlas

is a

community health data resource composited of more than 30 sources that helps

identify urgent, unmet needs in underserved communities. Equipping residents,

community organizations, and public health stakeholders with data to make

informed decisions leads to more impactful solutions and ensures that we are

spending our limited resources appropriately. Similarly, City Tech’s Connect

Chicago Innovation Program

has supported collaborative, community-led

ideas to increase technology access, digital skills, and adoption across

Chicago. Through the program, award recipients have created an affordable and

accessible cybersecurity

workforce development program

for women and leveraged data to create a neighborhood-level

tool

to understand gentrification and the displacement of community

resources. Efforts such as these can serve as examples of high-impact

opportunities for governments, private and public companies, non-profits, and

individuals to work together to create better solutions.

Collaboration across sectors and intentional innovation can address

the impending disruptions to our workforce and their economic ramifications – working

in siloes is no longer an option.

Path Forward

Where does this leave us? First and foremost, we are left with a

choice. We can do nothing, maintain the status quo, and leave ourselves

woefully unprepared for the impending disruptions and displacement while

inequality continues to deepen throughout our society.

Technological innovations and automation will leave millions of workers

permanently unemployed or underemployed, languishing in low-wage jobs without

hope of upward mobility and always one calamity away from financial ruin. Those

who are fortunate to find new jobs will struggle with volatile job transitions

as they navigate through our inadequate safety net, suffering from significant

reductions in income, insurmountable debt, and periods without access to

affordable health care, only to find their new job(s) pays a fraction of their

old wage, are unpredictable, and lacking quality benefits and protections. This

scenario would further diminish financial mobility, aggravate geographic

segregation, lower economic growth, and increase social divisions and public

health costs ( 104).

A small minority of survivors of the displacement fallout will

reap an even greater portion of the spoils, and the winners will be enticed to

sort themselves in protected bubbles with private communities, private schools,

private infrastructure, private clubs, and exclusive politics. As divisions

widen and partisanship intensifies, we will leave ourselves vulnerable to

crippling social unrest, rising class tensions, public health crises, populist

uprisings, an erosion of trust in public institutions, and increasingly

authoritarian politics ( 105).

Or, we can muster the collective will to take responsibility for

our futures and hold our public and private leaders accountable for delivering

a society that lives up to our ideals and provides every worker with the

opportunity to succeed.

We can use facts and data-driven evidence to

make smart decisions on which investments and interventions will best equip our

population with the necessary tools to thrive in the future and pursue healthy,

happy, and productive lives. We can implement economic development and social

policies that promote long-term economic growth, avoid zero-sum outcomes, broaden

the share of society’s benefits ( 106), provide

cushion from inevitable shocks that prevent financial and health disasters, and

allow all individuals to unlock their full potential, regardless of gender or

race. Even in 2020, I am optimistic that over the long run, the latter scenario

will prevail.

About the Author: George Letavish is the Manager of Solution Development at City Tech Collaborate. George works with teams made up of experts from the public, private, and nonprofit sectors, along with startups and universities, to execute pilots and implement technologies to benefit city residents across the world. Prior to joining City Tech, George was the Senior Policy Analyst at Get IN Chicago where he managed the lifecycle of grantmaking for programs serving at-risk youth. George previously worked as a policy analyst in the Illinois Governor’s Office and served in the United States Army as an intelligence analyst.